The need to be more ‘autonomous’ and ‘self-directed’ can be one of the more daunting challenges facing new TPG students, especially if you’ve been used to a greater level of instruction and guidance in your previous university experiences.

It’s true that at TPG level you’re expected to take more personal responsibility and initiative for your learning, but there’s a bit of a common misconception that this means you have to do everything yourself.

On the contrary, working collaboratively is a common feature of TPG study, and managing your relationships with other learners, as well as tutors and other staff, is an important element of being an autonomous, self-directed learner.

So what does being more autonomous actually mean? Let’s take a look.

The QAA Mastersness project defines autonomy as ‘[t]aking responsibility for [your] own learning in terms of self-organisation, motivation, location, working with others and acquisition of knowledge’ (QAA, 2014).

It’s important to understand that autonomy does not mean doing everything yourself. You’ll still have support, guidance and instruction from your tutors, supervisors, or other staff. It’s just that there may not be quite so much guidance and instruction as you’ve been used to in the past, and you might be expected to be more proactive in a lot of areas, including asking for any extra support you need.

In terms of your learning, there will still be classes and assessments and deadlines. But you might be expected to prepare more for classes and contribute to the discussions and activities taking place. And you may be expected to go off after the class and conduct your own further research into areas of interest or importance.

As for assessment, you’ll sometimes have more of a say in the focus of that assessment, particularly when it comes to choosing a dissertation topic. And when it comes to conducting research for your assignments, whilst you will still have lecture materials and resource lists to draw on, you’ll be expected to go beyond these basic starting points and to conduct more focused and rigorous research to inform your work. (links are to other TME content)

In both your learning and your assessment, you’ll need to be organised, and manage your time effectively. You’ll be expected to attend classes and make assessment deadlines or, where you can’t, to be proactive about following University and School procedures to catch up. If this sounds like a lot to take on board don’t worry – it’s a process, and you’ll become more comfortable with it over time. It’s all about being proactive and in control of your own learning.

It’s important that you have realistic expectations, both of yourself and others.

As regards the former, it’s natural to want to feel that you’re doing well from the outset. Nevertheless, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that there is a (sometimes lengthy) adjustment process for students transitioning onto taught postgraduate programmes. Accepting this fact and recognising that it’s ok not to be perfect and that you will grow into the role will significantly reduce the pressure you place yourself under, and ensure you are tackling challenges and setbacks in a more positive frame of mind.

Understanding what you can expect from tutors and other staff will also help you to navigate the uncertainties. As we’ve already seen, there is an expectation that TPG students show greater autonomy. How this manifests itself in terms of your relationships with tutors and staff will vary, and it can often be a good idea to explore potential ground rules in an early class.

Finally, you should think about your expectations of your fellow students. Giving some thought and planning to how you work and interact with your peers is an important element of expressing your autonomy and professionalism as a student. In some cases, you may be undertaking a group assessment where working effectively together will lead to better marks.

And even where there’s no assessment involved, working collaboratively with fellow students – both inside and outside of the classroom – is usually an enriching experience. So give some thought to what you’ll expect from your peers, and what they can expect from you. Don’t forget everyone is different, bringing different expectations and attributes to the table. Be open-minded in your expectations as to what individuals can contribute to the whole.

Develop a ‘check first’ approach. If you have a question about your course, try finding the answer yourself in the handbook or on My Dundee. If you can’t find the answer, ask someone – a tutor or classmate for example

Have a growth mindset. Base your expectations around the idea of improvement and don’t put yourself under pressure to be perfect. Set some modest goals as steppingstones to your ultimate targets

Network – work hard on your relationships with classmates, tutors and the wider university community. Over time you’ll identify a network of trusted collaborators and supporters

Becoming more confident in your ability to work autonomously and proactively is a challenge to be embraced, not feared. Not only will it make your time at university more successful and enjoyable, it will also allow you to develop a skillset that will be highly attractive for future employers, for whom autonomy is a highly sought-after graduate attribute.

Recognise that autonomy doesn’t mean going it alone – it means taking control of your own learning, whilst working effectively with peers and tutors and recognising when you need to ask for help or support.

At university – and particularly at postgraduate level – a lot of emphasis is placed on ‘being critical’ or ‘taking a critical approach’ but it can be difficult to know how you go about achieving that, particularly at first.

On this page we’ll explore what it actually means, look at ways of being more critical, and begin to explore what criticality might look like in the context of your subject(s).

What does ‘being critical’ mean?

In some ways the concept of criticality defies easy definition. A critical approach should run across much of what you do as a master’s student – from how you organise your time to how you engage with classes and study, and how you tackle assignments. For that reason, a simple definition can be misleading, or insufficiently thorough.

A useful way of trying to define what ‘being critical’ means at master’s level is to turn to the facets of taught postgraduate (TPG) study identified in the QAA Mastersness Toolkit. Criticality isn’t a facet in its own right – instead it permeates several of the areas identified in the toolkit.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it features strongly in the ‘Research and Enquiry’ facet, which is defined as ‘[d]eveloping critical research and enquiry skills and attributes’ (QAA, 2014). Likewise, critical thinking is also mentioned explicitly in the definition of the ‘Depth’ facet. But it’s also there implicitly in many of the other facets, such as ‘Abstraction’ (‘Extracting knowledge or meaning from sources and then using these to construct new knowledge or meanings’), ‘Complexity’ (‘Recognising and dealing with complexity of knowledge’) and ‘Unpredictability’ (‘recognising that real world problems are messy and complex, being creative with the use of knowledge and experience to solve problems’).

Two particularly important concepts in regard to critical thinking are analysis and evaluation. This short video provides a nice introduction to the role they play, and to the art of critical thinking in general.

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a useful framework to help us understand where criticality fits in terms of our learning at master’s level. Bloom identifies a hierarchy of learning, with lower order skills such as memorising and understanding and higher order skills such as analysis, and evaluation.

There will usually be some lower-order description and demonstration of understanding in the classes you take, the research you do and the assignments you write – the problem comes when your work never gets beyond that descriptive level.

So far, we’ve looked at criticality in a fairly broad sense. We’ve seen how crucial it is to many areas of master’s study, but how might you start to apply this important concept to your own field of study?

Whilst it’s impossible to get too far into specifics of different subject areas, we can pick up some very useful ideas from the Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF). In their descriptors for Level 11 (the level to which master’s courses are mapped), there are numerous references to criticality and critical thinking:

‘A critical understanding of the principal theories, concepts and principles.’

‘A critical understanding of a range of specialised theories, concepts and principles.’

‘Extensive, detailed and critical knowledge and understanding in one or more specialisms, much of which is at, or informed by, developments at the forefront.‘

‘A critical awareness of current issues in a subject/discipline/sector and one or more specialisms.’

‘Apply critical analysis, evaluation and synthesis to forefront issues, or issues that are informed by forefront developments in the subject/discipline/sector.’

‘Critically review, consolidate and extend knowledge, skills, practices and thinking in a subject/discipline/sector.’

‘Practice in ways which draw on critical reflection on own and others’ roles and responsibilities.’

In terms of learning then, there is an expectation that the research you conduct should be critical both in breadth and depth – you should have a broad critical understanding of the key theories, ideas, names and arguments in the field as a whole, and a deeper critical engagement with specific areas that you may be working on, and especially with the current debates in those areas.

More than that though, the final two points emphasise a critical approach to the very practices of your discipline – to not just what you study, but how you study.

Reflect upon a recent piece of work you’ve done, or something you’re working on just now. Where would you place that work on Bloom’s Taxonomy? Are you reaching the higher order skills – like analysis and evaluation – or does your work still tend to exhibit mostly lower order characteristics like description and demonstration of understanding?

Brainstorm the ways you could take a more critical approach in your classes, research, assignments and general master’s study. You might wish to use the QAA Mastersness Toolkit and/or the SCQF Level 11 Descriptors to help give you some ideas.

When you begin to study a subject, and particularly when you take the kind of critical approach we have been discussing in this resource, you become more than just a student – you become an active participant in that discipline, you become part of the conversation.

Taking a critical approach allows you to start reflecting upon and defining your professional identity. You can begin to identify arguments or ideas you are drawn towards, and those you find less convincing. You begin to define and communicate where your beliefs and values lie within the field. In short, you begin to take up a particular position within the discipline area.

This is not possible without a critical approach. If you merely seek to understand everything about your subject area, you will be knowledgeable but that knowledge will not get you terribly far. When you start to question beliefs, when you seek and interrogate evidence, when you synthesise and evaluate, then you become much more than a bystander – you become an active participant in your subject area.

Searching for and Assessing Sources

This section focuses on the research stage. We’ll highlight some of the things you need to think about when selecting your sources, and we’ll look at how you go about taking a critical approach at this early stage in the essay process.

Once you’ve broken down the question, you’re able to begin carrying out your research. The first step should be to brainstorm your ideas. The aim here is two-fold:

Armed with the answers to these two questions, you’re well placed to carry-out focussed and efficient research for your essay. We won’t go into detail on how to search for resources here – for detailed advice and resources, check out the subject guide(s) for your discipline.

Nowadays we have access to an almost endless array of different types of resource, and this can be both a blessing and a curse. Certainly, it’s easier than it ever was to access a wide array of potential sources but it also means there’s a greater danger of overwhelm and of encountering poorer quality material.

Allied to using reliable searches and databases and developing the research skills mentioned earlier, it’s important to be aware of the types of resource that are commonly used in your discipline. These may include:

So how do you decide which type of resource you can use when there’s so much to choose from?

Well, as you might expect, it’s not as simple as saying certain types of resource are suitable and other types are unsuitable. Different subject areas will use different resources in different ways, and to different extents, so you need to establish what the practice is in your discipline.

As you begin to read about and research your subject, pay attention to the types of resource these authors draw upon for evidence. This will help you to develop an understanding of the type of sources you should be using in your own research.

More than that though, the key is to develop a critical approach to the individual resources you encounter. Let’s look at some of the key considerations.

The first thing to consider is the question of authority. If you’re planning to use a source in your own work, you need to be sure of the author’s credibility in the field.

Look for the author’s affiliation – for example in journal articles you can usually quickly find out which universities the author(s). In books there will typically be an ‘about the author’ section.

This is what makes some websites, such as Wikipedia, so problematic from a research perspective. We simply don’t know who wrote or edited the material, and therefore can’t be sure of the authority of the work.

It follows, then, that related to authority is the question of bias.

Remember, the author of some resources (e.g. websites) might be organisations rather than individuals. In such cases, you have to consider any agenda such organisations may have.

Even academic authors may be coming from a very particular theoretical/ideological position, or in some cases their research may have been funded by organisations with a particular interest. This is not to suggest impropriety on the part of such academics, it’s just another consideration to be aware of.

Another key consideration is the date of publication.

In some cases, you may justifiably use resources dating back many years or decades. But in much research, particularly when you’re engaging with current debates or fast-evolving subjects, sources may quickly become out of date and superseded by more recent research.

Another factor to consider is the publisher of the source. Journals are usually published out of universities, and some may be more important or prestigious than others. Look out for a journal’s impact factor – this is a measure of the relevance of that particular journal within its field. The higher the impact factor, the more influential the journal.

Likewise, if your source is a book, is it published by a well-known, established publisher? It’s now easier than ever to self-publish online – again, that’s not to say all such material will be unreliable, but it should be part of your evaluation of that source.

Again, things get more complicated with websites. The websites of well-known organisations can be considered relatively reliable (but remember the point above about bias). Where you cannot identify the organisation or individual behind the website, then once again you need to be sensitive to the question of authority.

When you conduct research, you want to be sure that you identify any particularly influential or prominent work in the area. Once again, this is not to exclude other work which may be more recent or less established, it’s simply to ensure that your research is thorough and pays heed to the important voices or arguments in the field.

Some databases may indicate how many times an article has been cited in other publications. More broadly, you can look out for the same studies or names cropping up in your reading. This is a simple but effective indicator of which works are particularly influential in that field.

Good grades begin with good research. Using the appropriate search engines and databases, and learning how to frame your searches, will get you off to the best possible start by ensuring you access the most reliable and relevant resources. Taking care to evaluate and assess the credibility of these resources before you get too far into the reading will further ensure that your research is as focused and efficient as possible.

When you conduct research, it’s very likely that, no matter how well-refined your search terms are, you’re going to wind up with a long list of sources to work through. In many cases, the time constraints placed upon you will make it impossible to get through them all. A clear approach to identifying and critiquing resources is therefore vital.

The first step is to evaluate these sources and eliminate less promising material whilst identifying key material that you need to cover.

Once you’ve narrowed down your list of sources, the key is to read these sources actively rather than passively. We’ll look at some ways of doing that in the remainder of this article.

To manage the reading workload effectively and efficiently, you need to take an active approach to that reading. Reading actively means thinking about what you want to get out of a particular source and then seeking out that information, rather than reading passively and hoping the important information jumps out at you.

Start with what you already know. There is little sense in reading over and over, in different sources, something you already know or understand.

This should help you to identify what it is you’re looking for in the source in question. Ask yourself:

By taking this approach, you approach the source with a completely different mindset – instead of passively reading the text, you are interrogating it, looking for specific answers to specific questions.

When reading journal articles there are a number of things you can do to cut down on the amount of time you waste on irrelevant sources or information.

Begin by reading the abstract. This should give you an overall summary of the article, including key findings. Quite often you can come to realise a source isn’t going to be relevant simply from reading the abstract. And if it is relevant, often the abstract will guide you to the specific section(s) you need to read.

It pays to understand how journal articles are structured. This is particularly true in the sciences, where most articles will follow a predictable structure of introduction, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion. This may allow you to go quickly to the section you need rather than reading the whole thing.

Things are a little less predictable in the non-science subjects, but even then the abstract should give you a sense of how a specific article is put together and may allow you to quickly find the relevant parts.

Another useful technique is to begin by reading introduction and conclusion. Again this may allow you to identify key sections or to eliminate a source as irrelevant to your current research topic. But even if you need to read the whole article, having a sense of the conclusion you’re heading towards can help you make more sense of the content in the main body.

Finally, when you do identify the content you want to read in depth, make sure you take a critical approach.

There are also a number of things you can do when reading a book or chapter to take a more active and interrogative approach.

Most books will come with a contents page and an index. It makes sense then to start with these sections. the contents page will give you a sense of the structure of the book and may allow you to quickly identify relevant chapters or sections. You can use the index to scan for key words (perhaps related to the questions you’ve identified – see Reading with a purpose above). You may notice for example that your key words are clustered around a particular section of the book.

If it’s a chapter you’re focused on rather than the whole book, you may wish to start by reading the introduction and conclusion. As mentioned when we looked at journal articles, this can help you better understand the main body content, and may also allow you to focus on specific sections rather than the whole chapter.

Headings and subheadings are another useful way both of understanding the structure of the article (section headings are likely to identify key themes) and identifying specific sections which may be of relevance. You can scan these subheadings quickly before delving into any deeper reading.

If you do decide to focus on a specific chapter or section, reading just the topic sentences can also give you a good overview before you get into deeper reading. If the writing is well constructed, reading the first sentence of each paragraph will again help you to understand the general structure and themes, and to identify particularly relevant sections of the text.

Finally, when you’ve identified a chapter or section you need to read, you can scan or skim the text, looking for some of the key words or phrases you’ve identified. You may still need to read the whole chapter/section in more depth, but this approach may again save you some time in helping you to focus on the most relevant information.

It’s important to remember that reading for academic purposes is not the same as reading for leisure. You simply don’t have the luxury of reading everything from cover to cover.

By taking an active, critical approach to your reading you can learn to manage the workload and to find and extract information quickly and efficiently.

In this short resource, we’ll explore one possible approach for documenting and synthesising a large body of research

When you’re conducting research, it’s important to be able to both record that research and to synthesise your findings (to identify links between different sources). There are many different ways in which you can keep track of your activity, ranging from old fashioned pen and paper to referencing management software.

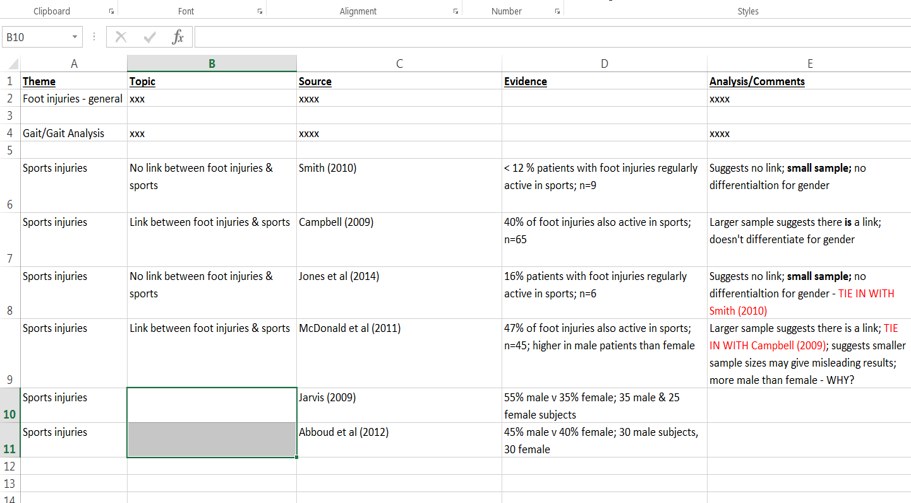

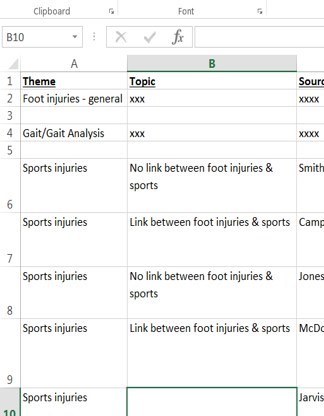

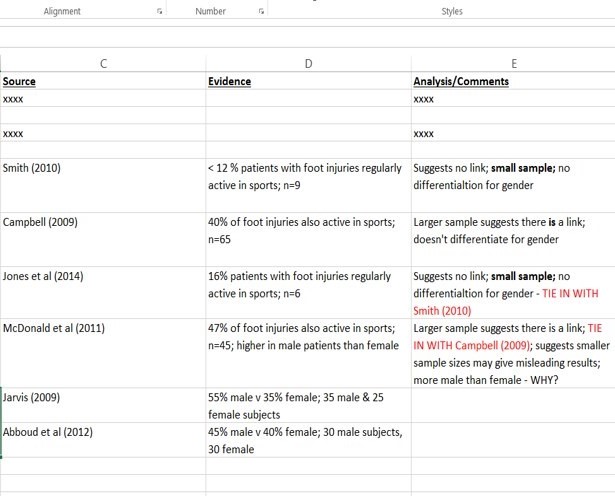

One quite useful way to get a broad overview of your literature and to begin to synthesise evidence around similar themes is to use a very simple spreadsheet.

In the example below, we’ve started to gather some ideas from our research into sports injury. The categories along the top allow us to start to think about synthesising and grouping evidence according to themes, dates, or whichever category is most appropriate.

These categories can be adapted in all sorts of ways to accommodate your particular needs and the level of detail you wish to capture on the spreadsheet.

As well as being useful in terms of recording and organising your research, this approach can help when it comes to writing up the research too – we’ll explore that next.

As we mentioned, you can adapt the heading on your spreadsheet to suit your needs. Here they’ve been set up to optimise a simple TEA model for writing paragraphs.

First of all we have the broad theme (column A), in this case Sports Injuries. This might relate to the an essay or chapter subheading, or even to the theme of the essay or chapter itself in a longer piece.

In the next column, we have the topics thrown up by the research. In this example, we have two – i) studies which show no link between foot injuries and participation in sports, and ii) studies which do suggest a link. Can you see how this format allows us to easily pull together similar topics/findings? These can form the basis of our topic sentences.

We have columns which list the source and detail the evidence from that source – perfect for our evidence element of TEA. And finally, we have recorded our own analysis and comments, which will form the basis of our critical commentary (the analysis in TEA). Again, note how easy the format makes it to link different studies and synthesise them in our writing.

Let’s take a look at how we can use this information to begin planning our paragraphs…

Topic…

A number of studies have been conducted into the links between foot injuries and sports participation.

Evidence…

Smith (2010) found that fewer than 12% of patients presenting with foot injuries also participated regularly in sports activities, in a study of 9 patients. Jones et al. (2014) identified a similar figure of 16% in their study of 6 patients.

Analysis…

The low rates suggest that there is little link between participation in sports and the occurrence of foot injuries. It should be noted, however, that these studies both had small sample sizes and made no distinction between genders.

Topic…

Indeed, larger-scale studies have found very different results.

Evidence…

Campbell (2009) found that 40% of patients presenting with foot injuries also participated regularly in sports, in a study of 65 patients. Similarly, McDonald et al. (2011) identified a rate of 47% in their study of 45 patients. They also identified a significantly higher correlation between sporting activity and foot injuries in male patients compared to female patients.

Analysis…

These studies cast some doubt on the earlier positive findings. It is notable that both studies draw on much larger sample sizes than those of Smith (2010) and Jones et al. (2014), perhaps suggesting that results in the latter were skewed by their small sample size. The findings of McDonald et al. that gender may play a role are also potentially significant.

A number of studies have been conducted into the links between foot injuries and sports participation. Smith (2010) found that fewer than 12% of patients presenting with foot injuries also participated regularly in sports activities, in a study of 9 patients. Jones et al. (2014) identified a similar figure of 16% in their study of 6 patients. The low rates suggest that there is little link between participation in sports and the occurrence of foot injuries. It should be noted, however, that these studies both had small sample sizes and made no distinction between genders.

Indeed, larger-scale studies have found very different results. Campbell (2009) found that 40% of patients presenting with foot injuries also participated regularly in sports, in a study of 65 patients. Similarly, McDonald et al. (2011) identified a rate of 47% in their study of 45 patients. They also identified a significantly higher correlation between sporting activity and foot injuries in male patients compared to female patients. These studies cast some doubt on the earlier positive findings. It is notable that both studies draw on much larger sample sizes than those of Smith (2010) and Jones et al. (2014), perhaps suggesting that results in the latter were skewed by their small sample size. The findings of McDonald et al. that gender may play a role are also potentially significant.

Notice how the paragraphs ‘speak’ back and forward to each other. For example, the final sentence of the first paragraph (small sample size) sets up the next paragraph (different results from lager samples), and the analysis part of the second paragraph refers back to the evidence from the previous paragraph. The final point in the second paragraph also suggests our next paragraph might be about studies that looked specifically at gender.

This is what gives your writing ‘flow’ but it’s hard to achieve this kind of structural coherence without planning things out first.

Seeing the bigger picture and synthesising your research is one of the keys to moving away from a descriptive approach to the evidence and instead taking a more critical and nuanced approach to that evidence and the role it plays in your writing.

There are many ways you can do this – perhaps you have some other tools in mind which will allow you to achieve this important task. But if not, the spreadsheet approach might be worth exploring.

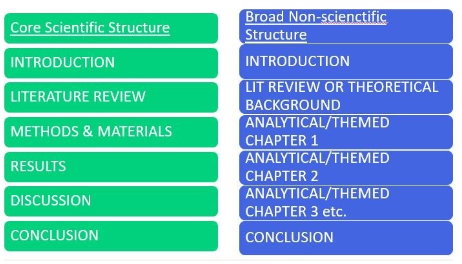

In this resource we’ll explore basic overall and paragraph structure for critical essays and papers.

Basic structure follows the INTRODUCTION-MAIN BODY-CONCLUSION format with which most people will already be familiar. In the sections which follow we’ll break down each of these three parts in a bit more detail.

It may seem obvious at first but when it comes to writing the introduction many people get confused as to what it should and shouldn’t contain, and how long or detailed it should be.

Your introduction is a key signpost – it tells your reader what the essay or paper is about, and how it will be structured. You do not want your introduction to take up a large proportion of your word count (the bulk of which should be spent on the main body). So avoid long explanations, definitions or background detail, and make sure you don’t start actually introducing evidence and arguments at this stage.

There’s no single correct way to write an introduction and to some extent the exact format will depend on the nature of the work and the conventions of your discipline. That said, adopting the following simple approach will stand you in good stead in most cases.

Begin by setting out the general context or subject matter of the essay or chapter. This will likely be a broad statement which gives your reader a sense of the general subject area to which the essay belongs.

Next, focus-in on the specific theme. Here you’re moving from that broad context above into the more focused concerns of the essay. What specific aspects or elements of the general subject area will you focus on? This will usually be determined by the demands of the question.

Finally, signpost how you will explore the question – tell your reader what you will cover in the order that you will cover it. This is an important step in helping your reader follow your line of argument.

The main body is the biggest and most important section of any essay or paper and is where you’ll organise your ideas and evidence into a coherent line of argument. Planning and structuring your main body is essential to writing a good essay.

One important means of keeping control of longer essays or dissertation chapters is through the use of sub-sections. Dividing longer pieces into shorter sections helps you to maintain control over both the content and the structural coherence of the chapter.

Sections and sub-headings also provide signposts and cues for your reader, making it easier for them to follow your arguments. Breaking the work into (logical) chunks and allowing your reader to pause between sections in this way is an excellent way of helping them to make sense of the text.

Paragraphs are another key means of controlling the structural coherence of your work. You should think of paragraphs as the building blocks of your writing. Each one adds to the strength and integrity of the overall structure.

It’s not enough simply to have a bunch of good paragraphs though – they also have to be organised in such a way as to flow from each other and give your writing that sense of logical flow.

The key rule to remember is 1 point, 1 paragraph. Each paragraph has its own job to do, its own idea or argument to evidence and elaborate on. If you try to do too much in one paragraph, your arguments are in danger of getting lost. Conversely if you don’t develop your paragraphs fully, then you’ll be left with little more than a list of bullet points rather than a well-argued essay.

There are many different ways in which you can construct paragraphs and indeed it pays not to be too prescriptive. It’s also likely that the paragraph structure will depend to some extent on the content and complexity of the ideas being explored. However, in many cases a very basic TEA model will be perfectly adequate and will ensure that you are writing well developed, critical paragraphs.

The topic sentence outlines the point or argument that you wish to explore in that paragraph. But it can also play an important role in linking this paragraph to the previous one, thus helping your writing to ‘flow’.

Once you’ve signposted the topic, present the evidence (with citations) that you intend to draw upon to help you make your point(s) or argument(s).

You’ve made your argument, you’ve presented your supporting evidence, now give your reader the analysis. Why do you think this is important or relevant? How does the evidence help you make your argument? What is it you want your reader to notice about the evidence you have just presented? This final step is often omitted but it’s what will make your work critical rather than descriptive. If you’ve ever had feedback that you’re not being critical enough or need to be more analytical, it’s probably this step that’s missing.

Topic sentence… Whilst the volume and range of material available online means it is easier than ever to conduct extensive research, it also means that the researcher can quickly find themselves overwhelmed by the amount of material they potentially have to work through.

Evidence… Jones (2019) found that a large majority of new students were unsure how to handle the vast number of search results they encountered when researching for an assignment, although the same study noted that as time progressed students had developed much more effective strategies. Meanwhile, Black and White (2020) argue that being overwhelmed by available resources leads to procrastination and students reverting to easily accessed generic resources such as Wikipedia.

Analysis… Whilst overwhelm is clearly an issue, the solution appears to lie in equipping students with the skills to find, sift and evaluate resources quickly and effectively. As Jones found, more experienced students did not suffer from the same difficulties, having developed an understanding of how to research more effectively and efficiently. Training students at all levels, but particularly near the start of their courses, in effective research skills would reduce the problem of overwhelm and help them to make better decisions about the type of resource they used in their assignments.

Whilst the volume and range of material available online means it is easier than ever to conduct extensive research, it also means that the researcher can quickly find themselves overwhelmed by the amount of material they potentially have to work through. Jones (2019) found that a large majority of new students were unsure how to handle the vast number of search results they encountered when researching for an assignment, although the same study noted that as time progressed students had developed much more effective strategies. Meanwhile, Black and White (2020) argue that being overwhelmed by available resources leads to procrastination and students reverting to easily accessed generic resources such as Wikipedia. Whilst overwhelm is clearly an issue, the solution appears to lie in equipping students with the skills to find, sift and evaluate resources quickly and effectively. As Jones found, more experienced students did not suffer from the same difficulties, having developed an understanding of how to research more effectively and efficiently. Training students at all levels, but particularly near the start of their courses, in effective research skills would reduce the problem of overwhelm and help them to make better decisions about the type of resource they used in their assignments.

You conclusion is your final chance to get your key messages over. It should contain no new arguments or evidence, but it should reinforce all the important points you want your reader to get out of the essay or chapter.

The conclusion is another example of where planning can help. If you plan out your essay or chapter before you start writing it, you can identify the conclusion you’re working towards, and that’s likely to give your writing much more of a sense of direction.

As was the case with the introduction, there’s no single correct way to write your conclusion. However, we would again suggest a fairly straightforward 3-step approach will work in many circumstances.

First, transition out of your main body and into your conclusion by reminding your reader of what the essay or chapter was about. This will likely relate back to the specific theme that you outlined in your introduction

Next, gather together your key findings. This is where you remind your reader of all the good analytical points you’ve made that help you build towards your conclusion. If you have used the TEA structure in the main body, these findings would relate to the key analytical points you came up with in each section.

Finally, provide a concluding sentence or two which broadens things back out into the wider context, and in doing so links back to the question you’ve been answering.

Taking some time to carefully plan your essay or chapter structure will mean you’re giving yourself the best chance of making your work as incisive and focused as possible. Consider breaking longer work down into sections based on key themes and use effective paragraph planning to unpack these themes in a cohesive and critical manner.

Writing at taught postgraduate level can be a daunting prospect, particularly if you have been out of higher education for a long time or if English is not your first language. There is often a fear factor around writing – and ‘formal academic writing’ in particular – which isn’t really warranted. In fact, there are a few basic conventions to follow – beyond that, there’s room for you to develop your own, confident voice and to let the quality of your research and your thinking shine through.

The purpose of any piece of writing you do at university is to convey your ideas and arguments as clearly and concisely as possible. It makes sense therefore to keep the process as simple as possible. Many people overcomplicate their writing, thinking that to sound ‘academic’ they have to write in an elevated style, using language and phrases that they wouldn’t normally feel comfortable using. Whilst there are certain conventions you need to follow, these are actually quite few in number and straightforward to apply. If you’re not confident in your writing, focus on understanding a few of these simple conventions and execute them as effectively as possible, then build from there.

Good writing very rarely just happens. Whilst we’d all love to be able to write just one draft of perfect prose, the truth is that writing is a messy process, and that planning, drafting and redrafting are all essential elements of producing writing of the standard expected at this level. When planning your assignments, you should always allow time for these stages. Writing that has been rushed in order to meet a submission deadline will rarely be of good quality.

Begin by planning your essay, paper, or chapter. How will you introduce it, what conclusion are you working towards, and what key points will you cover along the way (and in what order)? If you don’t have even this most basic of outlines in place, your writing is likely to meander towards a vague conclusion. By contrast, if you have a clear sense of the conclusion you’re writing towards, and of how you aim to reach that destination, then the writing will be much more focused.

You should see your first draft as just that – a first draft. Whilst you want the writing to be as good as possible, don’t be a perfectionist. Accept that at this stage the goal is to get you’re ideas down on the page, in some sort of coherent manner. You will make mistakes. That’s where redrafting, editing and proofreading come in. But you cant redraft, edit or proofread a blank page, so the first draft is about getting the ideas and arguments down in writing.

It’s at the redrafting, editing and proofreading stages that you will correct the errors, improve the writing, and make sure you are submitting a piece that’s written in an appropriate style.

In most academic writing, you will be expected to write objectively. This means using impartial language and avoiding sweeping statements, bias, and personal assumptions. You should avoid superlatives or over-emotive language and aim for a measured tone. This does not mean you can’t come to your own critical conclusions about the arguments or ideas that you encounter. It just means that you are arriving at a careful, critical evaluation rather than a subjective or uninformed opinion.

One key way to write more objectively is to write in the 3rd person, and to avoid the 1st person (I, we, our, etc.). For example, rather than writing:

I think the evidence proves that global warming is a real and urgent problem

you should use the 3rd person and write:

The evidence demonstrates that global warming is a real and urgent problem.

Can you see how the second version sounds more formal and authoritative? It’s still clearly your reading of the evidence, but it’s now written in a way that is much more formal and academic.

Note there may be occasions when you are expected or allowed to use the 1st person in an assignment, for example if you are being asked to write reflectively. In such cases, whilst it’s acceptable to use personal pronouns (I, we, our, etc.), you must take extra care that in doing so you don’t allow the writing to become over-descriptive and subjective. Most of the conventions mentioned on this page still apply to 1st person writing.

Another distinction to be aware of is that between the passive and active voice.

In the active voice, the person or thing (i.e. the actor) performing the action takes precedence. For example:

We conducted an experiment.

In the passive voice, it’s the event that takes precedence:

An experiment was conducted.

The passive voice always constructed of the verb ‘to be’ (in our example ‘was’) + the action in question (in our example ‘conducted).

Whilst it’s helpful for you to be able to recognise the distinction between active and passive voice in your writing, it’s not something you need to focus heavily on. As you may have noticed, the examples we looked at for 1st and 3rd person (above) are also examples of the active and passive voice respectively. That is to say, if you are writing in a formal, 3rd person style, it’s likely you will automatically be employing the passive voice, whilst reflective 1st person writing will employ the active voice.

At the core of academic writing is a formal style. Whilst this may sound daunting, it really boils down to following a few simple rules:

The one last thing which can adversely affect your writing is poor punctuation. Whilst there isn’t room here to go into detail about all the rules of punctuation, here are two key things to look out for:

You may be feeling a bit overwhelmed at all these conventions, all the things you need to remember. We can’t emphasise enough that the way to follow these conventions is to draft, redraft, edit and proofread. There are no short cuts – writing takes time, and involves a great deal more than just that one draft.

One final note on writing. One of the best ways of developing the skills you need to write in your subject area is to learn from the reading that you do. When you’re conducting research, don’t just read for content. Try to pay attention to the kind of language the authors employ. Look at how they use evidence. Note the ways they present their arguments.

If you find something particularly persuasive, clear or easy to read, try to work out why that was and look to emulate some of those things in your own writing. Likewise, if you find something difficult to read, try to work out why that is and avoid repeating that in your own work.

We’ve covered a lot of ground in this article and you may be feeling a bit overwhelmed by the challenge of writing academically. That’s understandable, but the key is to take things step-by-step. By mastering a few simple writing conventions and giving yourself the time and space to properly edit and proofread your work, you can develop confidence and skill in communicating your ideas clearly and appropriately.

And remember, you don’t have to master it all overnight – in fact none of us do. See it as a process, build on your successes and act on the feedback, and over time you should see your writing improve steadily.

One of the keys to writing effectively is to ensure that you write in grammatically coherent sentences. There are two particularly common sentence errors which can adversely affect the quality of your writing – run-on sentences and fragment sentences. In this short article, we’ll explore both in turn, looking at how to spot them in your own writing and, more importantly, how to fix them.

Before we look at run-on and fragment sentences, it’s important to understand the distinction between independent and dependent clauses.

An independent clause is a clause that can stand as a sentence in its own right.

A dependent clause is a clause that cannot stand as a sentence in its own right (to make any sense, it is dependent on another clause)

For example, the first sentence of this section comprises two clauses – ‘Before we look at run-on and fragment sentences‘ + ‘it’s important to understand the distinction between independent and dependent clauses‘

The first clause – ‘Before we look at run-on and fragment sentences‘ – is a dependent clause. It doesn’t mean anything on its own, it needs the second clause in order for it to make any sense.

By contrast, the second clause – ‘it’s important to understand the distinction between independent and dependent clauses’ – is an independent clause. If we took away the first clause, it could still stand as a sentence in its own right.

Once you recognise the distinction between independent and dependent clauses, you can easily understand and start to spot run-on and fragment sentences.

Run-on sentences occur when two or more independent clauses are joined together as one sentence, without the appropriate conjunction. For example, the following is a run-on sentence:

Design thinking is one way to foster effective leadership, this approach allows for a more agile and human-centred response to challenges.

Both Design thinking is one way to foster effective leadership and this approach allows for a more agile and human-centred response to challenges can stand on their own separate sentences. When they are joined together like this, they create a run-on.

We have 2 options if we want to fix a run-on sentence:

Option 1 – make them two separate sentences:

Design thinking is one way to foster effective leadership. This approach allows for a more agile and human-centred response to challenges.

Option 2 – change one of the clauses into a dependent clause:

Design thinking is one way to foster effective leadership, allowing for a more agile and human-centred response to challenges.

(In this example we’ve turned the second clause from an independent to a dependent clause – ‘Allowing for a more agile and human-centred response to challenges‘ would not now stand on its own as a sentence, it has become dependent on the preceding clause.

Fragment sentences occur when a dependent clause is treated as if it were independent. For example:

Design thinking is one way to foster effective leadership. Allowing for a more agile and human-centred response to challenges.

In this example, the first sentence is an independent clause but the second is not – it cannot stand on its own as a grammatically coherent sentence, it’s a fragment and to make any sense it is dependent on the clause which precedes it.

You may have noticed that fragment sentences are essentially just the reverse of run-on sentences. The good news is that once you learn to spot one, it’s likely you’ll also be able to spot the other. And the further good news is that our 2 options for fixing fragments mirror the fixes we’ve already seen for run-on sentences.

Option 1 – make them two separate sentences:

Design thinking is one way to foster effective leadership. This approach allows for a more agile and human-centred response to challenges.

Here we’ve simply rephrased the second clause so it does stand as an independent clause.

Option 2 – dock the dependent clause to the independent clause by making it all one sentence:

Design thinking is one way to foster effective leadership, allowing for a more agile and human-centred response to challenges.

Whilst the errors and rules we’ve discussed here can seem quite technical and impenetrable, once you understand dependent and independent clauses it becomes quite straightforward to understand how run-on and fragment sentences occur, and to spot them in your own writing.

These are by some distance the two most common sentence errors that crop up in writing at all levels. By being able to recognise and fix these errors in your own writing you will go a long way towards writing in the clear and effective manner expected of you at this level.

Editing and Proofreading Your Work

Editing and proofreading are key stages in the writing process (and they are separate stages) but they’re frequently rushed or missed out altogether. This is a failure of planning and time management. You should always build in time to properly edit and proofread your work. It’s very obvious to an experienced marker when it hasn’t happened.

Good writing rarely happens straight off the bat. Rather it’s a laborious process of crafting and recrafting until eventually you wind up with something you’re happy with. If you don’t take time to edit and proofread, it’s likely that you will be submitting sub-standard work.

It’s worth remembering that all the writing you encounter has gone through that same process. It may look effortless in its final form, but you’ll never see the graft that went into making it appear that way. If you don’t believe us, read this article by our Royal Literary Fund (RLF) Fellow, Chris Arthur. Chris is a professional essayist who also helped students with their writing during his time in his RLF role at the University of Dundee . His first paragraph on both the tribulations and the necessity of drafting and redrafting should provide comfort and instruction to us all.

You’ll find differing definitions of the distinction between editing and proofreading, and often there will appear to be overlap between the two. One possible way of thinking about it is in terms of structure and style. Editing is largely concerned with the former and proofreading the latter.

Whilst that’s possibly a slightly over simplistic way of looking at it, it does help give a sense of the distinction between the two tasks. Looking at it that way, editing is about the structure of the work both overall and in terms of paragraph and sentence structure. Proofreading on the other hand is about the fine detail. It’s about the spelling, the grammar, the syntax. It’s about consistency.

In some ways, the editing process begins at the planning stage. A plan allows you to think about structure and coherence before you start writing. Thus the more carefully you plan, the less editing you’re likely to need to do.

In terms of the editing itself, you might begin with your introduction and conclusion – are they effective? Does the former signpost to the reader the areas you go on to explore, and in what order? Does the conclusion follow naturally from the points you’ve explored in the main body?

Look also at paragraph structure – Is each of your paragraphs well-developed? Have you presented evidence and then unpacked or critiqued that evidence? Even scanning the pages quickly will give you a sense of paragraph length and may point to places where paragraphs look too long or too short. With longer paragraphs, make sure you’re not trying to cover too many points in the same paragraph – break longer paragraphs up where necessary. Very short paragraphs tend to suggest an over-descriptive approach and a lack of critical analysis. Do you need to go back and develop your arguments?

You should also try reading the first sentence of each paragraph (the topic sentence). Do they give an overall sense of the ‘narrative’? Do the points fit together in a logical order? Do you need to move anything around?

Proofreading should be the last stage of the writing process. But how do you know what to look for?

First of all, make use of the spell and grammar check functions on WORD or whichever programme you are using. You may also want to consider using the free version of a tool such as Grammarly. These will pick up many of the common errors in spelling, punctuation and grammar. Like anything else though, you have to use them critically. Don’t just accept the suggested changes without first considering whether they are valid. For example, WORD will often try to discourage you from using the passive voice when, in fact, it is quite common practice to do so in some academic writing. (You can read more about passive v active voice here).

Nowadays we have another option for proofreading our text - large language models such as ChatGTP. It's important to remember that these Generative AI models are still only tools, Our advice above stands - you must use them critically and you are the final human arbiter of what is right and wrong. See our section on GAI for more advice on how to use these tools ethically and effectively.

Regardless of whether or not you use an online tool, you should always manually proofread your work. There are lots of different techniques you can use. The Royal Literary Fund have produced this handy guide to proofreading your own work.

One thing you should always do when proofreading your work is pay attention to the feedback you’ve received on previous work from your markers, your supervisor, or other people.

It’s sometimes tempting to ignore or skim over the feedback, and it can be tough to hear about all the things we’ve done ‘wrong’. But instead of seeing feedback as criticism, try to look upon it as free advice on how to improve the work. Feedback is never personal – it’s a reflection on the work, not on you personally, and is offered constructively to recognise the things you are doing well and to help you work on the areas that need development.

So pay attention to your feedback and use it as feedforward for your future writing. And when you’re proofreading your work, be extra careful to check that you’ve addressed to the best of your ability the issues raised in that previous feedback.

By mastering a few simple writing conventions and giving yourself the time and space to properly edit and proofread your work, you can develop confidence and skill in communicating your ideas and your research in writing. And remember, you don’t have to master it all overnight – in fact none of us do. See it as a process, build on your successes and act on the feedback, and over time you should see your writing improve steadily.

For many students, one of the biggest concerns is understanding acceptable practice around academic ethics, and in particular plagiarism.

Although master’s students will be experienced in using and referencing sources, conventions can differ. It’s important therefore to understand exactly what you can and cannot do as a master’s student at the University of Dundee.

According to the University of Dundee’s Code of Practice on Academic Misconduct by Students, plagiarism is “[t]he unacknowledged use of another’s work as if it were one’s own”.

Plagiarism can include:

Using someone else’s words or ideas in your own work without acknowledging the source

Quoting someone else’s words without using quotation marks (even if you cite the source)

Substituting words rather than paraphrasing an author’s original idea (even if you cite the source)

Copying and pasting text into your own work without acknowledging the source.

This video explains how some of the more common types of plagiarism occur:

Plagiarism is one form of academic misconduct, but there are others you should also be aware of. These include:

Paying someone (an individual or an online company for example) to do an assignment for you.

Colluding with someone to produce a submission that is supposed to be your own work.

Re-submitting – partially or in full – a piece of work you have previously submitted for assessment at this or another university.

This is only a brief summary. You should read the Code of Practice in full to ensure you have a clear understanding of policy here at the University of Dundee. Every time you submit a piece of work at the University you’re confirming that you’ve adhered to this code, so it’s important that you know what it contains.

One particularly common cause of plagiarism is copying and pasting from other sources into your assignment document. This may lead to intentional plagiarism (where you knowingly and deliberately pass the copied content off as your own work) or unintentional plagiarism (where for example you subsequently forget to add the appropriate citations and references, or you include these details but fail to acknowledge with quotation marks that they are the words of the original author rather than your own).

In your previous studies, it may have been acceptable to use copied passages in this way, or else you may have been in the habit of copying directly into your assignment before editing the copied passage and adding the appropriate references.

You should never copy passages directly into your assignment. You should always think about why you want to use this particular piece of evidence, exactly which parts of the passage you need to include, and whether you should quote these parts directly or paraphrase (put into your own words).

Most assignments at University of Dundee are submitted through a piece of software called Turnitin, which produces what is known as a ‘similarity report’. It’s important to note that this is not a plagiarism report – there can be legitimate reasons for parts of your work being flagged up as similar to other sources.

Nevertheless, your marker will look into the highlighted extracts in more detail and make a judgement as to whether there is a problem. In all honesty, in many cases the technology is not required. An experienced marker will notice fairly quickly by themselves if something isn’t quite right.

In some subjects, you will be allowed to submit a draft of your assignment in advance of the deadline so you can see the similarity report for yourself and make any necessary adjustments. Note that this is not a universal option and is down to the discretion of the individual module leaders.

You will be informed if this option is available to you. If so, it’s important that you carefully consider what the report is telling you so you can take the appropriate action.

The exact penalties for plagiarism will depend to some extent on the policy within your School or discipline area and should be explained to you in your handbook and/or assignment information.

It is very likely that even minor or first offences will lead to some sort of reduction in the grade you receive for that piece of work. Major or repeat offences are likely to draw more serious penalties and can in extreme cases result in the termination of your studies.

You can read more about potential penalties in section 4 (Procedures and penalties) of the Code of Practice.

It’s understandable to begin a master’s course with a sense of trepidation about plagiarism and the ins and outs of referencing. It can all seem very confusing and fraught with danger.

But the truth is you shouldn’t spend your time on a master’s course worrying about plagiarism and obsessing about getting the details right. The ethical use of evidence and the referencing of that evidence are important elements of successful master’s study, but they are parts of a much bigger picture.

By understanding what constitutes plagiarism, and the role that referencing plays in ensuring that you don’t fall into that trap, you can spend less time worrying about how you reference the evidence and more time focusing on how you use that evidence to its best effect.

It’s likely that you are already familiar with the concept and practice of referencing. However, depending on where and when you previously studied, the requirements at master’s level in the UK may be different from those you have been accustomed to in the past.

At this level, there’s an expectation that you will reference accurately and appropriately. You’re expected to know what you’re doing, and plagiarism caused by careless or weak referencing is likely to be treated less sympathetically than at undergraduate level.

In this section, you’ll find the information you need to make sure you understand the basic requirements. We’ll look at the mechanics of referencing (the ‘how’) as well as exploring why referencing is such an important part of the work you’ll do at master’s level (the ‘why’).

Referencing is often looked upon with a sense of dread, but in essence it is a simple process and one that you can and should become competent at carrying out. Whilst you will need to invest some time to understand the process and some of its nuances, the basic mechanics of referencing are quite easily understood. Let’s explore these now.

There are numerous referencing systems and it’s entirely possible that you may have to switch between two or more during your time at university. Understanding the basic mechanics of referencing can help you to master individual systems and switch between them when required.

Irrespective of the system you are using, there are two steps you need to take: the citation and the reference.

Step 1 – the citation

The citation is the (usually brief) information you give in the body of your work, immediately upon using a piece of evidence. It will take the form of either:

an in-text citation, e.g. (Smith, 2020)

or

a footnote or endnote,

but never both. Which of these you deploy will depend on the referencing system you are using.

Step 2 – the reference

The reference is the fuller information about the source which you provide at the end of your work, in either a Reference List or a Bibliography.

A Reference List contains an entry (usually organised alphabetically by author surname) of every source cited in your work. A Bibliography goes further, containing not just sources you’ve cited but also sources from your wider research which have influenced your overall thinking, but which you haven’t cited directly in your work.

Again, the choice of Reference List or Bibliography will be dependent on the referencing system you are using and the conventions of your discipline. For more information, check out the subject guide(s) for your discipline.

Here’s a video from the team at Cite Them Right (the University’s recommended resource for referencing queries) highlighting that distinction between citations and references:

Now that we understand the basic mechanics of referencing, it’s important to understand why we need to reference at all.

Students can sometimes see referencing as a chore, and as something they have to do, rather than something that actually enhances or adds value to their work.

This is the wrong way to think about referencing. In any walk of life, being professional involves working within the conventions and protocols of that occupation. In academia, referencing and acknowledging your sources is one such convention. It’s not something that students alone have to do – it’s a practice we all have to adopt when we engage in any kind of research and writing at university.

Reasons to reference consistently and accurately include:

To acknowledge when we use the work or ideas of others

To display the depth and breadth of our research

To add weight and legitimacy to our own ideas and arguments

To refute or challenge an existing idea or argument

To ensure we are balanced and include an appropriate range of arguments and points of view

To place our own research in context

To allow our readers to further research the topic

When thinking about why we reference, many students tend to focus on the first of these reasons – we reference to show where our evidence came from so we don’t get accused of plagiarism.

But this is a very limited and unconstructive way of thinking about referencing. What you should notice is that many of the reasons listed serve to make your writing better and more effective.

By locating your ideas and arguments within the existing field of scholarship you demonstrate a deeper appreciation of your subject. By engaging with a range of ideas and arguments you make your own arguments stronger and more rigorous. And by pointing your reader towards the resources you’ve drawn upon you become an active participant in the research going on in that area.

So try not to see referencing as something you have to do, see it as something that adds significantly to the quality and depth of your work. Or to turn that on its head, realise that work which is not properly evidenced and referenced is intrinsically weak and unpersuasive, and certainly not of the standard we want to achieve at master’s level.

Practical ways you can develop your referencing skills

Look back at a previous piece of work you have done and assess how effectively you have cited and referenced the evidence you used. Is there an entry in the Reference List or Bibliography for every source you cited in the main body? Is there any evidence you’ve failed to cite?

Notice in the reading you do how evidence is cited and referenced, for example in a journal article or book that you read. Be aware that different publications will have different requirements (the variations in referencing are almost endless), so this won’t necessarily be the exact format you will be required to follow, but it will help you understand the mechanics of referencing, and the ways in which published writers in your field use evidence to support their writing.

At master’s level, it’s important to make sure that you understand how and why you need to reference. Getting into good practices in this area means you will avoid the risk of plagiarism, cite and reference accurately and efficiently, and in so doing enhance the quality of your work.

One of the challenges of academic writing is incorporating that evidence without losing the flow and general tone of your own words. Taking a little time to develop your confidence in the key techniques for incorporating evidence will greatly enhance the quality and coherence of your work, as well as helping you to cite and reference more effectively.

Essentially you have two options when referring to evidence - you can quote directly, or you can paraphrase (put the ideas into your own words).

Note that in both cases you need to cite the evidence – even if you put it into your own words, you are still using someone else’s ideas.

Different subjects have different conventions, so it’s very important that you establish what is preferred or permitted in your subject area.

For example, in the Sciences quotation is used very sparingly – the vast majority of the time you’d be expected to paraphrase. In other disciplines there will be more choice.

So how do you decide when to take one approach over the other? The video below provides some good suggestions:

When quoting directly, there are a few things to bear in mind.

First of all, how you lay out the quote will depend on its length. Shorter quotations (no more than 2 -3 lines in your work) should be included as part of the body of the text, and enclosed in single quotation marks. A short quote should never appear in your work as a freestanding sentence – it should always be part of a longer sentence.

Longer quotations should be presented in a separate, indented block, and do not require quotation marks. They should still however be introduced in the text which precedes them.

See examples of quote layouts - https://www.citethemrightonline.com/article?docid=b-9781350928060&tocid=b-9781350928060-setting-out-quotations

Generally, however, quoting large chunks of text should be avoided where possible, so consider paraphrasing instead or use selected extracts from the quote rather than the whole thing.

See examples of using extracts from quotes https://www.citethemrightonline.com/article?docid=b-9781350928060&tocid=b-9781350928060-making-changes-to-quotations

Paraphrasing can be a difficult skill to master but it is just that – a skill. With practice you can become confident in your ability to put other people’s ideas into your own words without falling into the trap of word substitution.

Word substitution (sometimes known as ‘paraphrase plagiarism) is where you leave the sentence as it is but change certain words to others with the same meaning. This is considered a form of plagiarism because you’re not really showing your understanding and synthesis of ideas – you’re simply showing your ability to find synonyms.

In addition, word substitution usually leads to torturous, clumsy sentences that are far less effective than the original.

The key is to understand that you are paraphrasing the idea or argument and not the sentence. Try thinking about how you would explain the idea to a friend, a tutor, or a family member without having the original text in front of you. This will allow you to move away from the structure of the original sentence and instead think about the underlying subject matter.

Have a look at our video below for more detailed advice on paraphrasing.

Regardless of whether you choose to quote or paraphrase your evidence, you will have two options in terms of how you present it – direct or indirect citation. Depending on the referencing system, this may affect the format and/or position of the citation.

Direct citation occurs when you refer to the author(s) directly in the sentence. The example below shows direct citation in the Harvard style:

Smith (2020) contends that the current penalties for weak or missing citations are too lenient.

Indirect citation occurs when there is no direct reference to the author(s) in your sentence. Note how in the Harvard system the content and position of the citation changes as a result:

It is argued that the current penalties for weak or missing citations are too lenient (Smith, 2020).

There are no hard or fast rules regarding whether to use direct or indirect citation; indeed, good writing will often intentionally combine both.

However, you should pay attention to the conventions of your discipline (for example when reading journal articles and books) and establish whether there is a preferred approach, or specific situations in which you would use one of these approaches over the other.

Practical ways you can develop your use of evidence

Identify the conventions in your own discipline regarding quotation and paraphrasing. It’s important that you know whether quotation is common or whether you’re expected for the most part to paraphrase. If you’re not sure, read a few journal articles or book chapters in your subject area and pay attention to how these authors present evidence.

Practice paraphrasing. It takes time to master, but once you do it will become a natural process and will add immeasurably to the effectiveness with which you use evidence, even if quotation is also permitted in your discipline.

Be aware of the distinction between direct and indirect citation, both in your own work and in the sources you read for research. Are there particular situations where one is more effective than the other?

It’s easy to get bogged down in details of specific referencing systems, and to worry about plagiarism. It is important to take care of these things, but beyond the basics the more important thing is how you’re using that evidence and how you’re incorporating it into your own writing.

By seeing that wider context, and by working on the craft of integrating evidence into your work, you can move beyond the basic concerns and start to see evidence – and the referencing that goes with it – as something that is part of a much bigger and more important picture.

At master’s level it’s common to have a dissertation or major project to complete as part of your course. Usually you’ll be able to choose your own question for such tasks, meaning that it’s a great opportunity to do some in-depth work in an area of particular interest to you.

This page will explore how to choose a topic and how to refine that initial choice down into a realistic dissertation or project question.

Most people will approach a major project or dissertation with some idea of what they’d like to do. But how do you know if it’s a suitable idea for a task of this length? And how do you choose between several different ideas, if you find yourself in that fortunate position? Use the checklist below to assess the suitability of your idea(s).

INTEREST – perhaps an obvious one, but you need to select a topic that’s going to keep you interested over a sustained period of time. Losing interest in a topic can lead to procrastination, a lack of motivation and, ultimately, a poor piece of work

NOT TOO BROAD – in all likelihood you’ll start out with a topic that’s too broad – this can leave you covering too wide a field, leading to unfocused research and a lack of critical depth in the finished work

NOT TOO NARROW – conversely, a topic can be too specific (although this is a much less common issue), in which case the research and the work you submit can be limited in scope

ORIGINAL – you need to have something original to say or do. Simply demonstrating knowledge and understanding of a particular topic isn’t enough at this stage. You need to be doing something more critical. Think ‘so what?’ – why does what you’re proposing to do matter?

ACHIEVABLE – you have to give yourself a realistic chance of completing the task within the deadline. You may have the perfect idea for a topic but how practical is it? For example, how easy is it going to be to get your hands on the resources you’ll need?

YOUR FUTURE PLANS- this one is often missed, but a big project such as this offers you a great opportunity to undertake some focused research in an area that might add to your future employability or even lead on to PhD research.

OTHER – these are some of the main things to think about but there may be many other considerations depending on the specific circumstances. Maybe you can think of some other criteria that are important to you?

Most people begin with a general idea of an area they’d like to research but, as we’ve seen, one of the big dangers is embarking on research with an idea that’s too broad and vaguely defined.

At best, it means you’ll spend a lot of time researching areas that won’t make it into the final work. All too often though, you’ll find yourself trying to cover too many of these areas, resulting in a final submission that is too general and lacking in criticality.

The first key step then is to shape the topic before you begin the research process. This will allow you to take a focused approach to both that research and the writing itself. So here’s a simple model that you can use to road test your ideas and make your topic more focused and critical…

Let’s take a look at each of these elements in turn:

TOPIC – your likely starting point, but often too broad and wide ranging to make a suitable dissertation or project topic without some refining.

FOCUS – what specific aspect of your chosen topic do you wish to focus on?

RESTRICTION(S) – what restrictions or limitations are you setting for yourself? A good way of narrowing down and refining a topic, restrictions are often geographical (focusing on one particular country, or comparing/contrasting two specific countries) or temporal (e.g. focusing on a specific time period) but many other types of restriction can be used.

INSTRUCTION – what is it you’re actually proposing to ‘do’ with the topic (e.g. are you comparing and contrasting, analysing, critiquing, evaluating?) This is the element that will give your dissertation its critical focus.

Breaking the question or topic down like this is a good way of ensuring you have a topic that meets the criteria we identified earlier. It also helps ensure you don’t waste time at the outset by casting your research net too wide.

Let’s take a look at an example of how this process might work in practice (note the example which follows is for illustration purposes only and is not necessarily a valid dissertation topic):

“I want to do something on social media.”

Ok, you have a topic but that’s about it. If you were to start a literature review with just the topic ‘social media’ you would be overwhelmed, and if you did manage to produce a dissertation or project it would be far too broad. Can you be a bit more specific? What’s your focus?

“All right, I want to look at whether social media can be used as a design tool.”

A bit better – at least we now have an angle or focus. But it’s probably still too broad. Could you apply a restriction to help you focus in a little more?

“Ok, well I guess I’ve become pretty interested in how I’ve been using social media as a design tool over the last few years, so I suppose I’m focusing on higher education?”

Much better! Now you’ve refined the topic down from something very broad to something that’s much more focused and critical. One more step. What is it you actually propose to do with the question? You’ve said earlier you wanted to look at whether it could be used as a design tool – does this give you a clue?

“Well, I suppose it means I want to come to some sort of judgement about whether or not social media can be used as a design tool in higher education. So I guess I’m evaluating its effectiveness?”